|

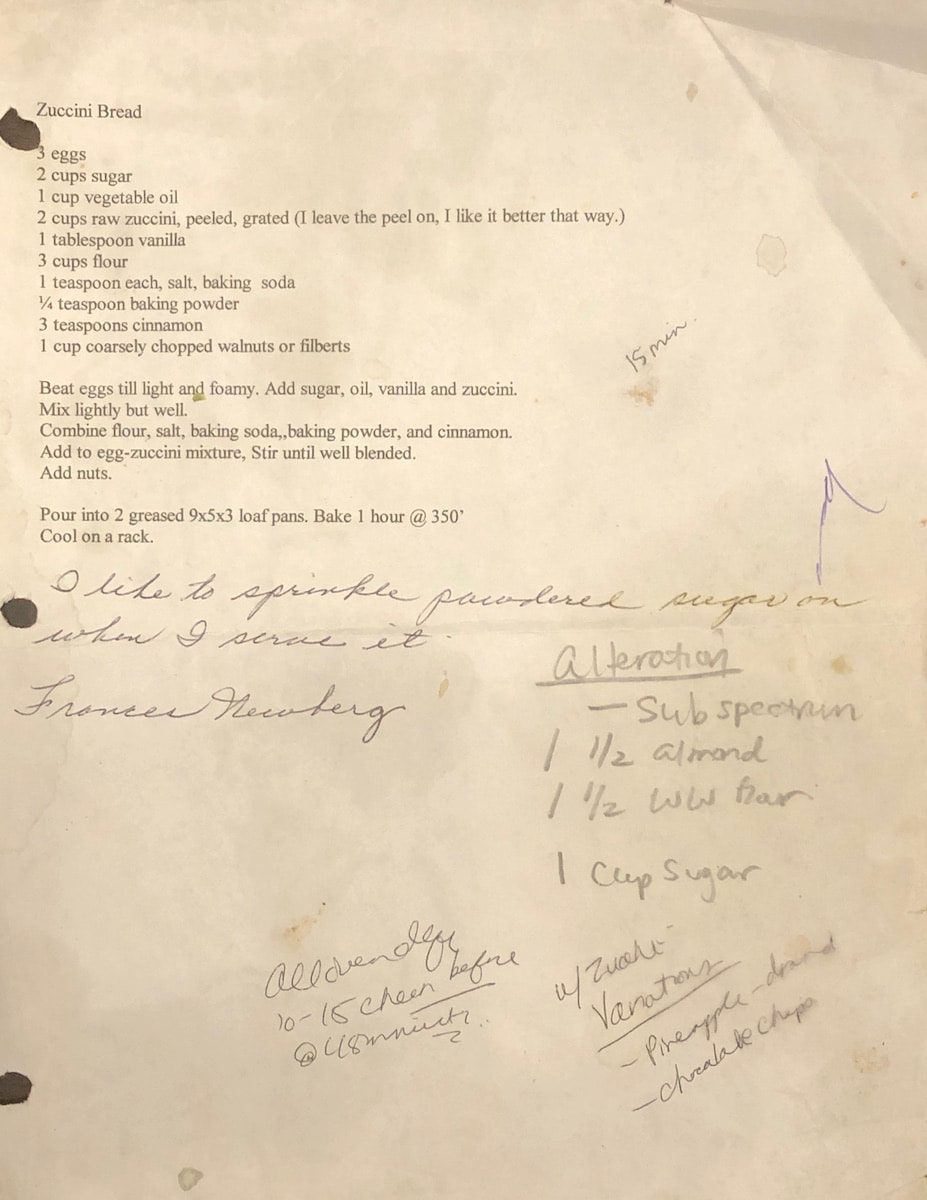

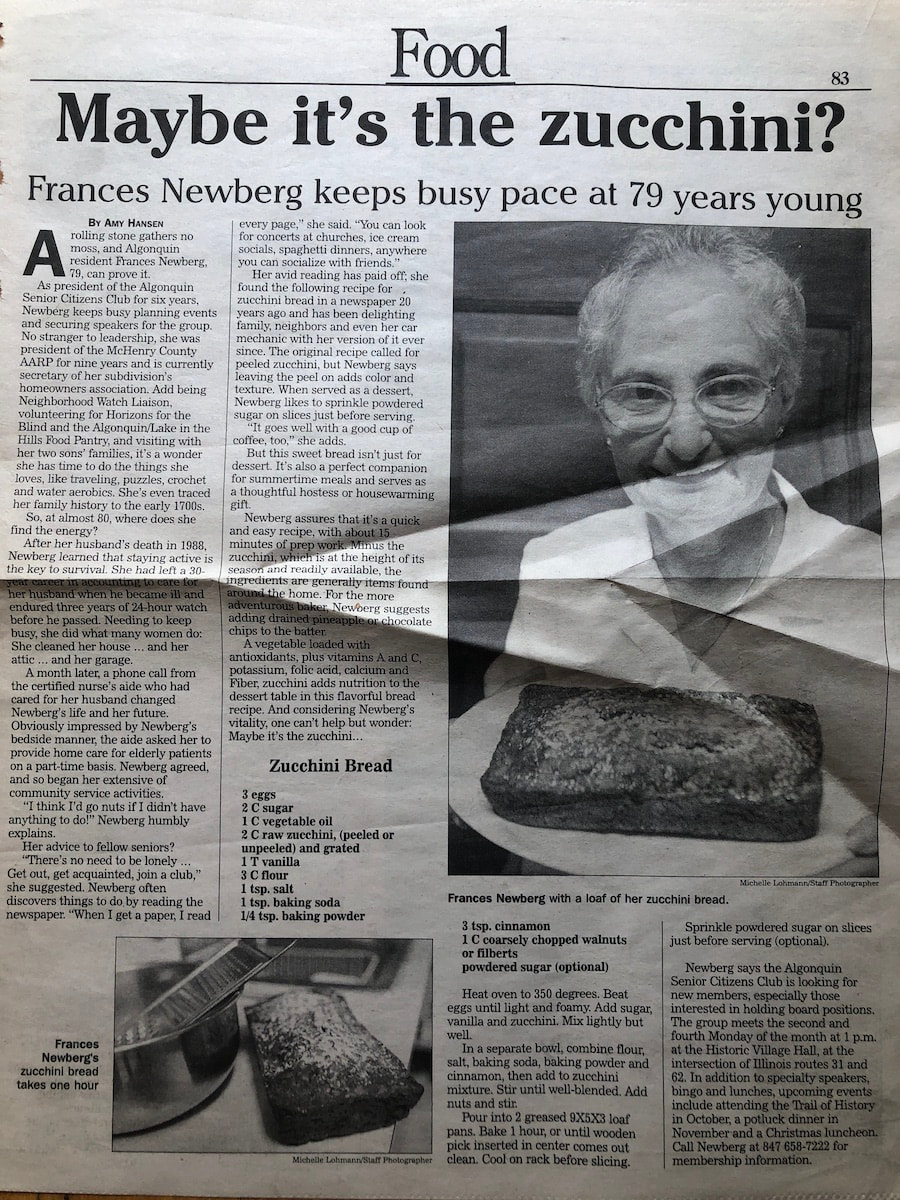

There’s a special spot in my heart for zucchini bread. Because it’s the epitome of summer abundance. It’s what Midwesterners bake midsummer when we’re up to their eyeballs in zucchini; the deep, green-skinned squash reproduces like rabbits and manifests literally overnight. Because it’s the multi-tasking superhero of baked goods: breakfast, dessert, and afternoon snack too. Because it’s another really tasty way to eat your veggies. But mostly, because it was the first recipe I featured on the Pioneer Press Food Page, my first professional gig as a freelance writer. THE BACKSTORYTwenty years ago, I was newly married and relocating to a new city. I was also aspiring to become a writer, after leaving the security of my short post as a high school English teacher. With my English degree and clips from my college newspaper, I planned to freelance for Pioneer Press, a group of weekly local newspapers in the Chicago suburbs with a main office based in my new neighborhood. Early in June, the managing editor sent me out on assignment—a News piece about heavy construction on a main thoroughfare—and then, after my story ran, I never heard from him again. Self-doubt ensued, and I figured I’d have to switch tactics. And I definitely questioned the whole “I’m going to be a writer” thing. Just when it seemed to be a dead end, the editor called in late August to apologize for not getting back to me sooner. He’d been busy mentoring summer interns, he explained. But the college kids had all gone back to school now, and he was in desperate need of a freelancer. Specifically, he needed someone to write the Food Page. Historically, the Food Page featured a local person of interest and seamlessly segued into a featured recipe. My editor had secured the first interview subject for me—a 79-year-old woman named Frances Newburg from the local seniors club and her prized recipe for zucchini bread—but after that, I’d have to find my own stories. I remember calling Frances and setting up the interview. To my surprise, she invited me to her home, so I could see the garden where she grew the zucchini, and of course, taste her homemade bread. That day, after touring her beautiful, well-maintained backyard garden, we sat at her cozy kitchen table, where I enjoyed a slice of her extremely moist zucchini bread and furiously jotted down shorthand. We chatted about her involvement in the senior club and what it meant to her. She advocated for seniors to stay active in their communities as the key to longevity. I remember marveling how sprite and full of life she seemed at almost 80. I wondered if her secret was in fact the zucchini, and I even put that detail in the title of the article. During our chat, she handed me the typed recipe for zucchini bread (she spelled it zuccini) with a handwritten postscript : “I like to sprinkle powdered sugar on when I serve it,” followed by her signature.  This is the article that ran in Pioneer Press Algonquin Countryside in September 2004, almost 20 years ago. You can tell it's one of my first articles because I use "Amy Hansen" as my byline. A short while later, I decided my name was too boring, and I needed to add my middle name. Amy Gail Hansen has been my name in print ever since. Unfortunately, it got a bit wrinkled in storage. Frances was my first food page interview, but certainly not my last. I went on to feature countless others, including:

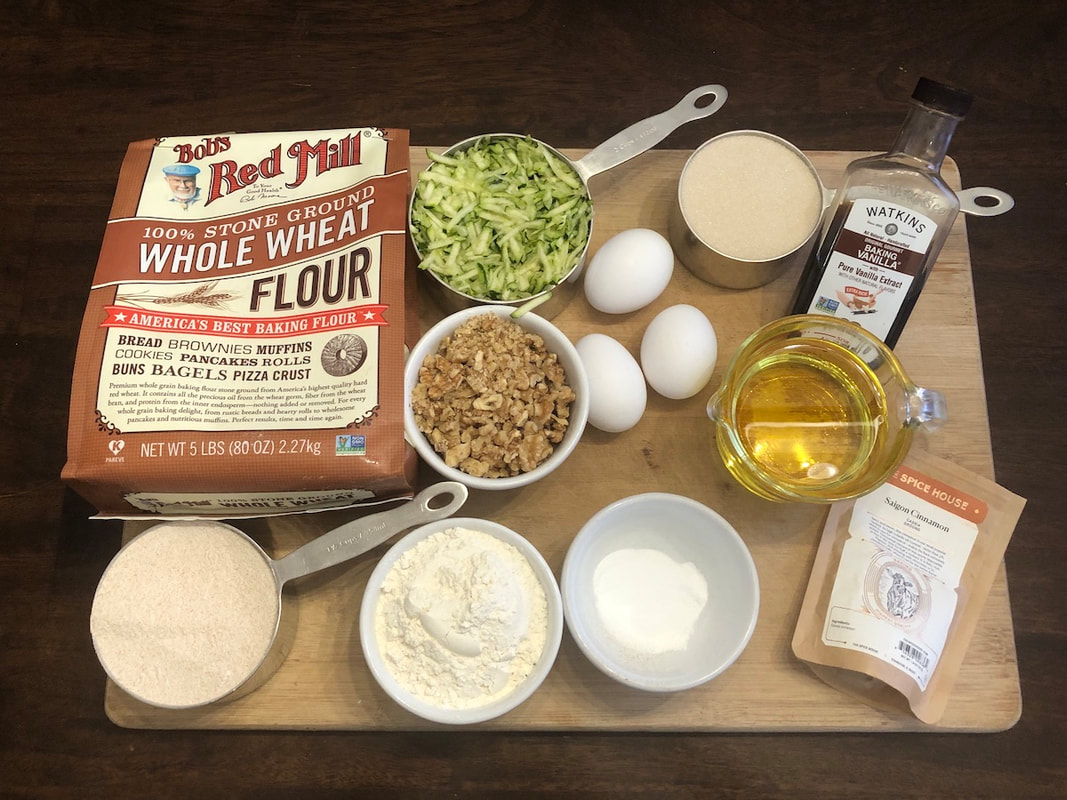

Looking back, this Food Page was such a slice of Americana, offering Midwest staples, ethnic specialties, and beloved family traditions. I am honored to have listened to and shared these stories of everyday heroes making a difference in their communities and the food they held close to their heart. This humble start writing the Food Page sparked my career in journalism. Soon, I was writing for the Diversions Arts & Entertainment section of the newspaper, interviewing literary gods like Wally Lamb, Elizabeth Strout, and Jane Hamilton; musicians like Chubby Checker, and filmmakers like Christopher Coppola (AKA Nicholas Cage’s brother). Getting paid to write and boasting a byline made me believe I was a “real” writer. I even had business cards to prove it. And this belief fostered the confidence to later accept a job with Triumph Books to write two biographies about singer/songwriter Taylor Swift, and subsequently, to write my debut novel The Butterfly Sister and get it published by William Morrow/HarperCollins. Success begets success. That’s why, twenty year later, my zucchini bread recipe is my most cherished entry in my personal cookbook. Because it marks the start, the seed that blossomed into this career that keeps evolving but ultimately, feeding my soul. It is fitting that I am now writing a food blog and finishing a second novel heavily influenced by food that will include recipes. Everything comes full circle. Looking at the recipe now, I see I added some notes in my own (sloppy) handwriting from our conversation that day in Frances’ kitchen. Frances mentioned that oven temperatures vary and suggested bakers should check on the zucchini bread loaves after 45 minutes in the oven to avoid over-baking. She also suggested two variations, the addition of chocolate chips or drained crushed pineapple. Over the years, I have made my own edits and variations to this recipe. This, in my opinion, is the beauty of recipes. Like humans, they can and sometimes have to adapt. And often, those adapations reflect our values, our family customs, our religion, our medical needs, our personal tastes, or our current pantry inventory. INGREDIENT SWAPSThe Flour So how have I adapted Frances’ Zucchini Bread recipe over the years? For starters, because I enjoy eating the most healthful, natural and least processed foods, and I know the benefits of 100% whole grain wheat flour, I’ve tinkered with the flour ingredients. I’ve found the most foolproof way to add whole wheat to most baked goods is to use it at a 50/50 ratio with all-purpose (AP) flour. For example, if a recipe, such as this one, calls for 3 cups of AP flour, you can use 1 ½ cups AP flour and 1 ½ cups whole wheat flour. If you push that percentage to more than half, you’ll have to adjust other aspects of the recipe to control texture, taste and baking time. Keeping half AP flour means people accustomed to the taste and texture of traditional white flour baking will still enjoy your bread and may not even notice a difference, while those who enjoy the nutty taste and hardier texture of whole grains will appreciate the extra nutrition and depth of flavor that whole wheat flour brings. I have tested this ratio with baked goods over the past decade—from quick breads to cakes, from cookies to hamburger buns—and it has never failed me. I even made a half whole wheat Danish Kringle this past Christmas (blog post pending) and it was perfectly divine. The Sugar Another adaptation to this recipe reflects the health of both my husband and daughter, who both have type 1 diabetes. In my opinion, there is way too much sugar in most quick breads and cakes. They’re often so sweet, you can’t taste the star ingredients, like the banana or zucchini or chocolate or carrot. So I employ a 50% ratio when it comes to sugar too. I have researched and tested this time and time again, and can attest that that you can remove up to half of the listed sugar in most baked goods recipes without changing any of the baking chemistry, and still end up with a delicious lightly sweetened baked good. Like the AP flour, if you remove more than half of the sugar, it gets complicated and your chances of the baked good coming out with the right taste and texture decreases . Frances’ original recipe called for 2 cups of sugar, which I reduced to only 1 cup. This bread tastes perfectly sweet in my opinion. If you find this is not sweet enough to your tastes, you can try using 1 ¼ or 1 ½ cups sugar instead. But I urge you to use the 1 cup sugar I suggest, and see if you really notice the difference. The Oil Finally, as I age, I’ve had a harder time digesting some fats. This is common during perimenopause, as women don’t produce as much stomach acid to digest foods, specifically fat. The original recipe calls for vegetable/canola oil, something I don’t even keep in my pantry anymore. I find that when I eat baked goods with canola oil, my stomach actually gurgles from trying to process the fat. Recent studies have identified this type of oil to be highly inflammatory. Plus, there’s this oily, stick-to-the-roof-of-your-mouth film that I taste in breads and cakes made with canola oil (originally called rapeseed oil—they changed the name in 1978 to make it sound more enticing to consumers. The Can of Canola stands for Canada, where this plant is largely grown and processed). So I swap the oil out in this recipe with Spectrum organic all-vegetable shortening (palm oil). I measure it out into a glass measuring cup and melt it in the microwave, then let it cool slightly before adding it the recipe. Sometimes, I also use coconut oil, but this does add a subtle hint of coconut flavor, something I love but others may not. Baked goods made with this spectrum palm oil have a really "clean" or "healthy" not oily taste. One ingredient I definitely keep in the recipe is the cup of chopped walnuts. (Frances suggest walnuts or filberts, otherwise known as hazelnuts. I’ve never tried that before.) Zucchini bread without nuts is good, but the nuts make it great in my opinion. It adds texture and diversity in every bite. TEST KITCHENThere is a final ingredient I need to mention and that’s the zucchini itself. Zucchini bread is long associated with summer, because that’s when zucchini is in season. But I’ve been able to procure fairly good tasting zucchini year round, and often very inexpensively. Specifically, Target and Aldi carry two-packs of zucchini that I often also use for grilled zucchini boats for about $1-$2 this time of year. If you’re okay eating vegetables brought in off season from Mexico, zucchini bread can be enjoyed all year long. Reflecting on the zucchini bread I made over the years, I remember thinking it “turned out” better a longer time ago, and I couldn’t figure out why. I ran through the recipe steps trying to discern what had changed for me over the years. And then it hit me. In 2004, when I first interviewed Frances, I had yet to fully grow as a cook/baker and did not have the kitchen appliances and gadgets I do now. When I initially made her zucchini bread, I used a box grater to grate the zucchini because that’s all I had. Of course, I later invested in a food processor, which is essential for so many recipes, and I began using it to grate the zucchini. And that’s just around the time I started finding the resulting bread less tasty. So I put this to the test. I made two batches of this bread—one with box grated zucchini and the other with zucchini grated on the food processor. And then I had my husband and children taste both breads, without telling them which was which. (Very scientific, I know.) The verdict? Mixed results. Three of us preferred the box grated, and the other two preferred the food processed one. I found the box grated bread to be moister, but others claimed the same for the food processed version. To be honest, they were both tasty and everyone ate both pieces. Other factors might affect moisture as well, like the zucchini itself and the baking time. So maybe in the end, the way the zucchini bread is grated doesn’t actually matter. It's likely a matter of taste. THE HISTORY OF ZUCCHINI BREADBecause I currently travel to Chicagoland libraries, women’s groups and historical societies to present Food History, from "Duncan Hines: More Than Cake Mix" to "Sweet Treats of the Midwest," I would be remiss not to end this blog post with a bit of the backstory on zucchini bread itself. Of course, I can’t talk about the history of the bread without first reviewing the history of zucchini itself. According to Susan R Singer, Department of Biology at Carleton College in Northfield, MN, the word zucchini is Italian in origin. It comes from the word zucca, which means squash. The Italians first cultivated zucchini, then immigrants likely brought it the United States in the 1920s. It is a cucumber/squash hybrid and thus, also related to melons. So how did this vegetable become a beloved quick bread? According to Lauren Cabral from Back Then History, it’s existence derives from the Middle Ages tradition of vegetable based puddings, but it didn’t become popular until World War II. During this time, Victory gardens allowed people to grow their own food to save costs, and zucchini was a star of these gardens, because as we know, it is an abundant crop. Hippies in the 1960s pushed for healthier, vegetable-based foods and zucchini bread grew again in popularity. Like banana bread or pumpkin bread, it’s a “quick bread” so it’s easy to make, can be frozen, and doesn’t require frosting. And FYI, National Zucchini Bread Day is April 25th. Since we’re talking history, I must share that while writing this blog post, I decided to Google Frances Newburg and see if, by chance, she was still alive. Unfortunately, I found her obituary. She passed in 2018, but lived to be 93 years old. I still think the zucchini had something to do with that. THE RECIPEZucchini Bread (Adapted from Frances Newburg) Makes one Bundt cake or two 9 by 5 loaves (16-20 servings) PRINT RECIPE (PDF) Ingredients: 3 eggs 1 C. sugar 1 C. palm oil or coconut oil (melted and cooled slightly) 2 C. raw zucchini, grated 1 T. vanilla extract 1 ½ C. all-purpose flour 1 ½ C. whole wheat flour (I use Bob's Red Mill) 1 tsp each salt, baking soda ¼ tsp baking powder 3 tsp. cinnamon (I use Spice House Saigon Cinnamon) 1 C. walnuts, chopped Powdered sugar, optional for dusting Directions: Preheat oven to 350 degrees F. Whisk eggs until light and foamy Add sugar, oil, vanilla and zucchini. Mix lightly but well with a rubber spatula. Combine and whisk together flour, salt, baking soda, baking powder and cinnamon. Add flour mixture to the egg-zucchini mixture. Stir with rubber spatula until blended but do not over-mix. Gently fold in nuts. Pour into one Bundt pan or two 9 by 5 loaf pans (greased). Bake 35-45 minutes for Bundt and 40-60 minutes for loaves. Bread is done when inserted toothpick or cake tester comes out clean. Cool on a wire rack for 15-20 minutes. Slide a butter knife around the outer edges of the cake and the edges at the center tunnel. Then place a plate on top and flip it over. A good Bundt pan should release the cake easily. Continue cooling on plate.

Sprinkle with powdered sugar. Slice and enjoy!

0 Comments

|

Amy Gail Hansenis a novelist, professional public speaker and food blogger obsessed with exploring new culinary adventures while preserving kitchen traditions of the past. THE BACKSTORY KITCHEN provides the inside scoop on everything food, featuring reviews, food history anecdotes, original recipes and solutions to common problems in the kitchen. Upcoming EventsMonday May 6, 2024

@ 7pm Indian Trails Library (Wheeling, IL) Sweet Treats of the Midwest REGISTER Wednesday, May 8, 2024 @ 1:30 pm Geneva Public Library Sweet Treats of the Midwest REGISTER Tuesday May 21, 2024 @1pm The Hadassah Society Temple Beth Israel Skokie, IL Duncan Hines: More Than Cake Mix Thursday May 23, 2024 @ 6pm Oak Park Public Library Duncan Hines: More Than Cake Mix REGISTER Tuesday June 18, 2024 @ 7pm Palatine Public Library Duncan Hines: More Than Cake Mix Thursday June 27, 2024 @ 7pm Elmhurst Public Library Duncan Hines: More Than Cake Mix Tuesday July 9, 2024 @ 2pm Park Ridge Public Library Sweet Treats of the Midwest Thursday, Sept. 5, 2024 1:30 pm Vernon Township Community Service Building | 2900 N. Main Street, Buffalo Grove Sweet Treats of the Midwest Wednesday October 16 @ 6pm Villa Park Library Sweet Treats of the Midwest Monday, November 4, 2024 @ 1pm Prospect Heights Public Library Sweet Treats of the Midwest Wednesday Feb 12, 2025 @ 1pm Glenview Park District The Eastwing Wing Senior Center Sweet Treats of the Midwest Thursday July 17,2025 @6pm Creekside Cookers Del Webb, Elgin, IL Duncan Hines: More Than Cake Mix Archives

April 2024

Categories |